Scenes are the building blocks of stories. Scenes tend to be 500 to 2,500 words long, and an average novel has fifty to sixty scenes.

Scenes weave the reading experience. No matter how well-designed your story structure and how interesting your characters are, if your scenes don’t work, readers won’t enjoy your story.

Every scene builds towards the story’s climax, but every scene is a tiny story in itself. Like stories, scenes have a beginning, a middle, and an end. The scene begins with a character who wants something. During the middle, the character struggles to get what she wants. And at the end, the character gets what she wants. Or she doesn’t.

And like stories, scenes need to introduce change, be it an internal or external change. A scene needs to move the story forward or reveal character. Best if they do both.

Scene Structure Templates

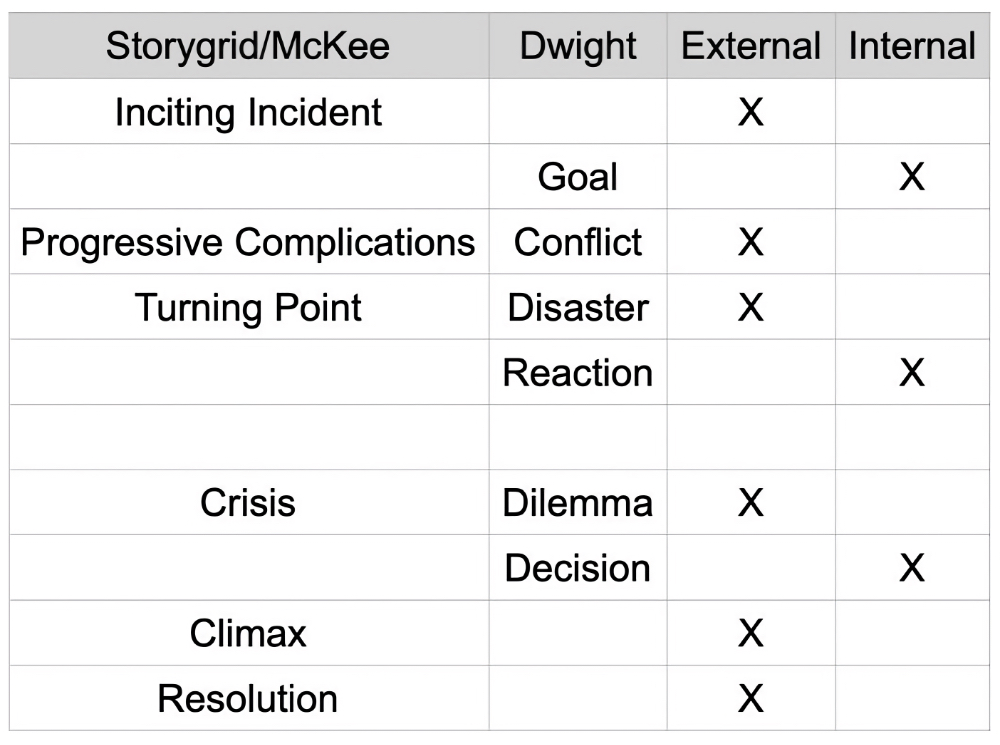

The two most famous scene structure templates are the five commandments and the turning point by Robert McKee and Storygrid and the scene-sequel approach by Dwight V. Swain.

Here are five commandments and the turning point of McKee and Storygrid:

- Inciting Incident

- Progressive complications

- Turning Point

- Crisis

- Climax

- Resolution

The inciting incident, turning point, and climax are the most crucial scene elements. Remember that a scene needs to introduce a change? The turning point is the moment when the change takes place. External changes don’t suffice. The POV character needs to be in a different emotional state at the end than at the beginning of the scene. Readers want to know how the turning point impacts the POV character. Dwight V. Swain recommends writing scenes and sequels. Dwight’s scenes have the following elements:

- Goal

- Conflict

- Disaster

Sequels have the following elements:

- Reaction

- Dilemma

- Decision

Some of those elements sound like commandments, don’t they? If we compare the five commandments and the scene/sequel elements, we get the following table:

If we were to combine Dwight’s scene and sequel elements into one scene, we’d get a five-commandment scene without the inciting incident, climax, and resolution but with three additional elements: the goal, reaction, and decision. The goal, reaction, and decision define internal movements, which the five-commandment scenes neglect.

The Eight Crafts Scene Structure

The Eight Crafts scene structure has nine scene elements:

- Scene orientation

- Stimulus and stakes

- The POV character’s scene goal

- Progressive involvement

- Stake flip (aka turning point)

- Reflection (internal turning point)

- Climactic action

- Outcome

- The POV wrap-up

The scene orientation shows when and where the scene takes place and in which POV we are. Without the scene orientation, readers might get confused.

The term stimulus and stakes takes the differences between stories and scenes into consideration. A story’s inciting incident is a powerful event that throws the protagonist’s life out of balance. That doesn’t happen in common scenes. Scene stimuli can be as tiny as a thought.

The stimulus puts something at stake and unravels until it flips those stakes. The five commandments allow the turning of any value. Better to flip or turn stakes relevant to the scene or genre.

Not all scenes progressively complicate things, some scenes introduce positive changes for the protagonist. Progressive involvement is a more neutral term.

The stimulus unravels until it flips the external stakes. The stake flip forces the POV character into an introspection. The POV character needs to come up with something to save the day. During the reflection, the following happens:

- The external stake flip causes an internal stake flip. For instance, the POV character changes from confident to scared. This is important. The external stake flip relates to the POV character. She needs to be in a different emotional state at the beginning and the end of the scene.

- The POV character contemplates the nature of the stimulus.

- The POV character has an insight or discovers a tool or a key ability. If there is more than one way to save the day, the POV character faces a crisis.

- The POV character decides what to do and modifies the scene goal, taking her realization, the tool, or the key ability into consideration.

The POV character comes out of the reflection with a decision. The decision takes the POV character into the climactic action. She either succeeds or fails, which becomes the scene outcome.

Remember POV characters need to be in a different emotional state at the beginning and the end of the scene? The scene outcome is an even stronger stimulus than the external stake flip. Hence, the POV character’s response to the scene outcome needs to be on the page too. Also, you can use the POV character’s response to wrap up the scene and make it memorable.

More details in The Eight Crafts of Writing and topics like antagonistic and protagonistic scenes, scene building blocks, the stimulus-response mechanism, scene types, how to structure chapters, and the scene-train technique.